Navigating the Modern VC Ecosystem: Risk vs. Return, Misconceptions, and Skill vs. Luck

Addressing Evolving VC Trends & Fundamentals

👋 Hello friends,

Thank you for joining this week's edition of Brainwaves. I'm Drew Jackson, and today we're exploring:

Evolving VC Trends & Fundamentals

Key Question: What emerging trends or underlying fundamentals are influencing the modern venture capital ecosystem?

Thesis: By understanding the optimal number of investments to maximize returns, misconceptions about the industry and the players in it, and the drivers of returns for successful venture capital firms, we can better understand and achieve success in this rapidly evolving industry.

Credit Carta

Before we begin: Brainwaves arrives in your inbox every other Wednesday, exploring venture capital, economics, space, energy, intellectual property, philosophy, and beyond. I write as a curious explorer rather than an expert, and I value your insights and perspectives on each subject.

Time to Read: 14 minutes.

Let’s dive in!

Venture capital has rapidly evolved and expanded throughout the last couple of decades into a full-fledged industry. Throughout its development, many of the core characteristics and fundamental properties of the industry and the players within it have drastically changed to fit emerging trends, shortcomings, and ultimately increase success rates within the industry.

As such, our knowledge of the modern principles and aspects of the industry may be missing key developments or potentially may be fundamentally skewed by our historical thinking.

The purpose of this essay today is to continue to acknowledge and address some of the aspects of the modern venture capital industry and any misconceptions we may have, revolving around three key questions:

Why don’t VC firms invest in more companies?

What misconceptions are present about what people do and don’t do in VC?

How much do VC returns reflect superior skill and strategy compared to market timing or a fortunate “home run”?

View part 1 of this series here.

Credit Carta

Why don’t VC firms invest in more companies?

In essence, this question is addressing the balance between quantity and quality.

Let’s start with the facts. Once a venture capital firm has raised its fund, let’s use $100M for our purposes today, which constrains the actions they can take. For instance, according to traditional time frames (depicted here), they are going to invest those funds over the first 1-4ish years of the fund, then hold their investments for 3-7ish years, then exit their positions.

Besides the fund deployment timeframe, the number of employees is usually relatively constrained to a certain size. In our example, given a $100M fund, the venture capital fund will receive $2M in management fees per year to help make and support the investments.

The goal of the capital gained from management fees is to simply keep the venture capital firm afloat, covering all of the necessities, but not necessarily turning a large profit. As you would imagine, there are many different things that will feed into this number: rent, utilities, software licenses, travel, legal fees, outsourcing, research databases, expert testimonials, and most especially, salaries.

Given all of these costs, the amount of money left per year to allocate to salaries is relatively constricted, meaning that our venture capital firm couldn’t just hire 200 people at $100k a year each (that would be $20M in salaries per year) - that is, unless they want to go in debt, which is another beast altogether.

So, we’re going to assume a relatively small staff to work on and deploy investments in our fund. Each of these staff members will have a limited amount of time to work on finding and enacting investments (there are only 24 hours in each day for everyone). As such, there’s a total amount of time (let’s call it T) that is derived by multiplying the average amount of hours worked per person over the fund's life, multiplied by the number of people (T = # of Total Hours Per One Person * # of People). For our purposes today, let’s say T = 10,000 (even though in reality it would be much larger).

Now we get to our battle of quantity and quality. Working with our total manpower time T, we can dissect (given arbitrary values) how we can best invest that time in our investments, given the quality and quantity tradeoff. Let’s assume the following:

Low-quality investments take 10 hours each

Medium-quality investments take 100 hours each

High-quality investments take 1000 hours each

Now, these are arbitrary benchmarks, but they serve our purpose well. As you can see, if you were only to prioritize low-quality investments, you could end up with 1,000 low-quality investments (100k on average). Similarly, you could end up with 100 medium-quality investments ($1M on average) or 10 high-quality investments ($10M on average).

Which option is the best?

That depends on who you ask. Jerry Neumann strongly believes in the high quantity of low-quality investments approach:

Most VC funds are far too concentrated in a small number (<20–40) of companies. The industry would be better served by doubling or tripling the average # of investments in a portfolio, particularly for early-stage investors where startup attrition is even greater. If unicorns happen only 1–2% of the time, it logically follows that portfolio size should include a minimum of 50–100+ companies in order to have a reasonable shot at capturing these elusive and mythical creatures.

However, the answer is much more complicated than this. It differs across asset classes and even within asset classes. Within venture capital, some will stray towards the high-quality end of this scale, performing fewer investments that are “better.” Likewise, some migrate toward the low-quality end of this scale, performing more investments that are “worse.”

If you had to take an average of the entire venture capital industry in comparison to other asset classes, given our simplistic framework above, the venture capital industry would probably fall into the medium-quality investment bucket.

Why aren’t they in one of the other buckets?

The simple answer is just that there are already other players in each of the other buckets, meaning that if venture capital wanted to be in one of them, it could simply be a different industry. For instance, angel investors traditionally make a ton of small bets in the hopes that one will go big; private equity traditionally makes a small number of big bets in the hopes that one will go big. In this case, venture capital is just the middle option, a more equal balance between quantity and quality.

For a more long-winded explanation, we need to get into the juxtaposition between winner dilution and positive Black Swan exposure.

According to Nicholas Taleb’s philosophy in his book, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, venture capital firms should be trying as much as possible to expose themselves to positive Black Swan events. In this case, this would amount to having as many tiny bets in as many companies as possible (for a 0.1% stake in a $100B+ company is better than larger stakes in smaller companies).

However, some have argued that this strategy will be ineffectual in practice because of resource limitations (as discussed above), but also due to the dilution of winners. If a fund invests in an excessive number of companies, even if it picks a few winners, the impact of those winners on the overall fund’s return can be diluted by the sheer volume of average or failing companies.

Venture has opted to settle in the middle, where they want as much exposure to positive Black Swans as possible, but they want to retain as much ownership as possible in every company as possible. This way, when they win, they win big (but also lose big).

Additionally, with a larger investment usually comes a larger measure of control over the strategic direction of the company (if wanted, some venture capitalists take a hands-off approach). Some venture capital firms have argued that this elevated level of control can increase the likelihood of outsized returns.

Again, this balance is incredibly complicated and differs greatly between each firm, depending on the risk and reward preference of that firm.

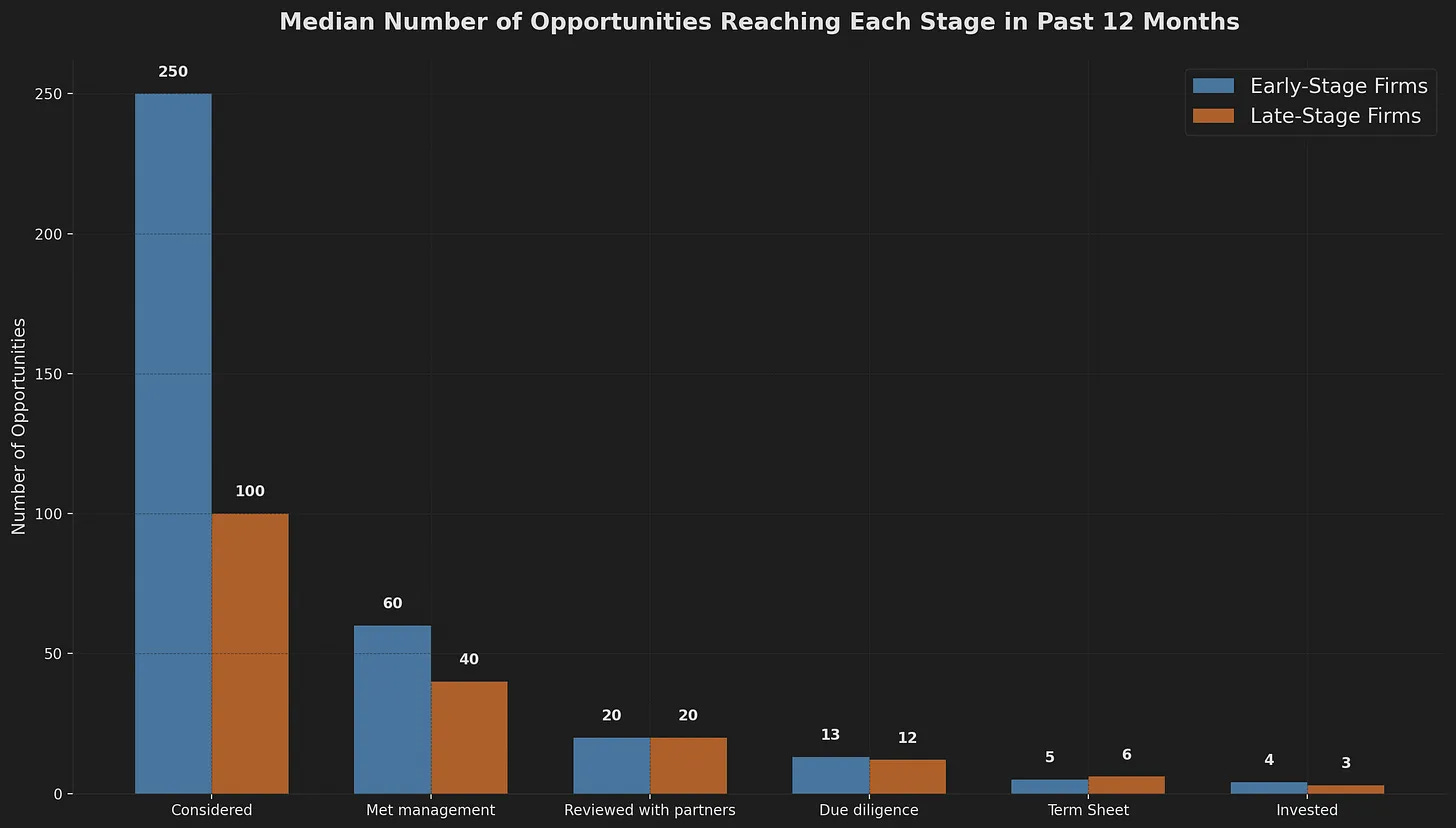

Michael Tefula, in his publication VC Mastery, in a 2024 article, cites studies from Harvard and Stanford that surveyed hundreds of VC funds to understand their typical deal funnel. Their summaries are shown in the graph below:

Credit VC Mastery

As we’ve discussed, the venture business is very much a numbers game. Everyone is striving to find the optimal mix between quality and quantity while constrained by their unique limitations. How many investments are “enough”? It’s tricky to say.

Credit LinkedIn

What misconceptions are present about what people do and don’t do in VC?

One of my earliest articles was a surface-level piece surrounding this topic, entitled: Things I Wish I Knew Going into Venture Capital. In it, I discuss a couple of misconceptions I had about the field of venture capital before going into it. They included the following:

You need prior job experience

Sourcing investment opportunities is incredibly difficult

Venture capitalists work all the time

Getting a job in venture capital is super competitive

Venture capital firms prefer to hire from target schools

This information, while helpful, is mainly targeted at students and entry-level people interested in becoming a part of the venture capital industry.

I was recently reading through some of Jerry Neumann’s past work, and I stumbled across this article he wrote in 2010, titled Prepping for a Meeting With Someone Who Wants to Become a VC. It provides a more targeted list of 8 common misconceptions present about what people do and don’t do in the venture capital industry.

Of the 8 “myths” he presents, I want to highlight two major points he addresses:

In venture capital, I will get to build great companies

In venture capital, I will get to shape the future

To start, many venture capitalists come into the industry with the hopes and expectations of being able to build great companies. This isn’t necessarily the case.

Entrepreneurs and founders build companies. So, technically, venture capitalists don’t build companies. But they can help advise and consult on the construction of the company and the strategic direction in the future. As Neumann writes, “If you find yourself building the company, you’ve invested in the wrong entrepreneur.”

In this case, venture capitalists perform much more of a support role than an action-oriented role. It’s similar to how some limited partners are to their venture capital general partners, where they can provide advice and information based on their experience (usually what made them the money that they’ve invested in the VC firm), but they aren’t actually handling the day-to-day management of the fund.

As a venture capitalist, you aren’t the primary driver of innovation or the creator of value. That’s the entrepreneur. You’re simply helping them get the tools necessary to streamline their task.

Similarly, it’s often a mistake for venture capitalists to enter the industry hoping to shape the future. Again, this is a nuanced misconception.

As Neumann writes, “VCs don’t decide which companies get started, entrepreneurs do.” In other words, venture capitalists don’t drive the beginning of the funnel in the idea creation phase. Instead, they react to what’s already been founded, what ideas are being pursued, and figure out which one of these they want to fund.

So, in a way, they technically are shaping the future by acting as a sort of natural selection barrier to the ideas and entrepreneurs that pop up, deciding whether or not they are able to get assistance to pass Go. But, their powers are limited to what’s founded in the first place, so technically they aren’t shaping the future in its entirety as they’re subject to other market factors.

There’s no doubt they have a rather large influence on the future, but are they the ones shaping it? Not necessarily.

Besides what I’ve brought up in my articles and what Neumann adds, there are a few more misconceptions present within the VC industry that should be addressed:

VCs just give you money

VCs know everything about running a startup

In reality, venture capital firms do provide capital (money), but this often comes with a value-add component and an oversight component.

Many venture capitalists have prior experience either running or being a part of a company within the industry they invest in, or they have prior experience investing in or advising companies within the industry they invest in, so they can often provide strategic consulting to their portfolio companies.

This can include strategic advice, introductions to potential customers or partners, help with recruiting, and guidance on how to raise subsequent funding. Most aim to be more than a bank, acting as partners in growth.

Additionally, as a condition of giving your company money, venture capitalists will take an equity share and often a board seat, which gives them influence and oversight on their investment. They want you to succeed, so they are there to offer advice, but also want to make sure that success is possible and the company is on the right path.

Although venture capitalists may have worked or ran a business in the industry your company is in and they have prior experience investing in and advising companies within this industry, that doesn’t mean they know everything about running a startup.

Usually, their deep expertise lies in identifying market opportunities, evaluating business models, and scaling companies. Often, however, they do have a lot of surface-level expertise on many things, but their deep expertise is limited.

Overall, there still continue to be many misconceptions about what venture capitalists do and don’t do in their jobs.

Credit Toptal

How much do VC returns reflect superior skill and strategy compared to market timing or a fortunate “home run”?

This question reflects two fundamental arguments about venture capital returns: the first being the influence of luck and skill on investment outcomes, and the second referring to whether some firms are “better” than others at the skill-based portion of the total return profile.

In other words, if luck is entirely the driver of all venture capital returns, there will be no portion attributed to skill, and therefore no firm is inherently better than another at this process. If, instead, skill were the entire driver of venture capital returns, it would come to be the reason that we could attribute those firms with better returns as being “better” VC firms.

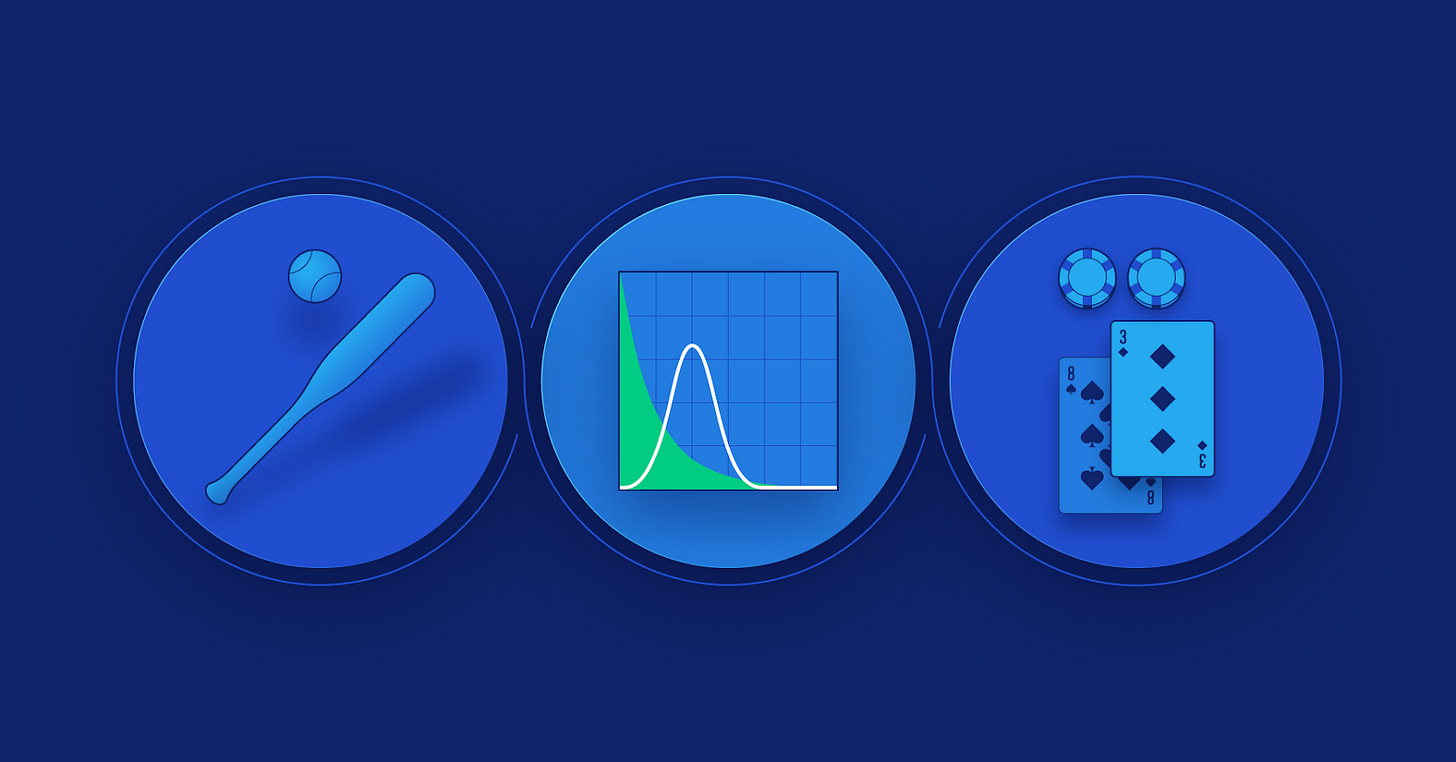

Luck plays a role in every aspect of life in some way or another. Michael Mauboussin, in his 2012 book, The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing, describes how luck and skill fall onto a continuum where some activities are all skill and no luck, some are no skill and all luck, and most fall somewhere in between.

Mauboussin provides the following “test” for whether something is entirely luck-based: “ask whether you can lose on purpose. In games of skill, it’s clear that you can lose intentionally, but when playing roulette or the lottery, you can’t lose on purpose.”

In venture capital, you can lose all of your money on purpose with a relatively high certainty in many cases. As such, there must be some aspect of skill present in venture capital.

It’s unclear what the exact proportion of luck and skill is (on average) in venture capital, but two well-known studies help provide some clarity on this aspect.

A 2006 Harvard Business School working paper by Gompers, Kovner, Lerner, and Scharfstein found some interesting conclusions on the role of luck and skill for entrepreneurs and venture capitalists.

Successful serial entrepreneurs are more likely to replicate the success of their past companies than either single-venture entrepreneurs or serial entrepreneurs who failed in their prior venture.

As for venture capitalists, when investing in first-time entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs who previously failed, more experienced venture capital firms were shown to have higher success rates on their investments in comparison to less experienced firms.

Interestingly, the study additionally found that when investing in entrepreneurs with a track record of success, experienced and inexperienced investors had the same success rates. In this case, the entrepreneur’s skill carries the investment’s success and whatever skill the venture capital firms had wasn't significant.

So, from this study, we can conclude that there are some realms where a venture capitalist’s skill is impactful on the success of the investment. However, there are realms where the skill is irrelevant, where the success is almost entirely luck-based.

A 2018 paper published in the National Bureau of Economic Research by Nanda, Samila, and Sorenson provides further clarity.

Through their analysis, they found that successes in venture capital were mainly driven by investing in the right place at the right time. However, they found that venture capital firms “do not persist in their ability to choose the right places and times to invest.”

This suggests that there is less skill involved than we might be led to believe, for if there was skill involved, the repetition of investing at the optimal time could be replicated.

Additionally, they found that initial successes improved future access to deal flow, which in turn enhanced the odds of investing in quality investments, thereby perpetuating successful performances. In other words, if you get the first fund correct, it becomes easier and easier to be successful in subsequent funds.

According to these researchers, picking those original winners appears to be mainly a matter of luck.

While not encompassing or empirically verified, these studies begin to cast aspersions on the thought that venture capital investments are mainly due to skill. In fact, it seems as though many of the returns are attributable to luck rather than the skill of the investors.

Credit Alumni Ventures

Navigating the Modern Venture Capital Ecosystem

The venture capital industry is no longer the niche domain it once was. It’s a rapidly maturing force, constantly adapting to new market dynamics, trends, and technological advancements. As we’ve explored, understanding these shifts, particularly the optimal number of investments to maximize returns, misconceptions about the industry and participants, and the drivers of returns for successful venture capital firms, is crucial for anyone seeking to thrive in or simply comprehend this complex ecosystem.

Venture capital firms face a difficult decision when balancing the quality and quantity of investments, given their self-imposed resource limitations. Other asset classes have chosen to fall in different places on this continuum, with venture somewhere in the middle. Moving to one side or the other can vary risk levels and reward levels; for instance, moving to the quantity side of the scale increases exposure to Black Swan events but can lead to winner dilution, negating many of the positive side-effects.

Whether you are in the industry, planning on entering, or simply observing it from afar, the venture capital industry is rife with misinformation and misconceptions. Unfortunately, venture capitalists aren’t directly building great companies (they merely provide advice) and aren’t actively shaping the future (although they do influence it). Furthermore, they aren’t just giving you money (they provide many “value-add” services) and they don’t know everything about everything (although they will act like they do).

Finally, while many venture capitalists, writers, and other industry players will strongly argue, skill seems to be dramatically less of a factor in whether an investment is successful or not. While returns aren’t entirely luck-based, research has found that there are many circumstances wherein skill is not a differentiator between return profiles. The ability of funds to consistently achieve outsized returns is almost entirely attributable to probability distributions (i.e., if you were to run the simulation 1000 times, there would be around that many that could randomly guess and be successful).

The venture capital industry will undoubtedly continue to rapidly evolve (the only constant is change). By understanding a few of the core dynamics—the drive for optimal risk and reward balance, misinformation about the roles played in and around the industry, and the role of luck and skill in investment successes—we can better anticipate future trends and navigate this ever-changing landscape.

That’s all for today. I’ll be back in your inbox on Saturday with The Saturday Morning Newsletter.

Thanks for reading,

Drew Jackson

Stay Connected

Website: brainwaves.me

Twitter: @brainwavesdotme

Email: brainwaves.me@gmail.com

Thank you for reading the Brainwaves newsletter. Please ask your friends, colleagues, and family members to sign up.

Brainwaves is a passion project educating everyone on critical topics that influence our future, key insights into the world today, and a glimpse into the past from a forward-looking lens.

To view previous editions of Brainwaves, go here.

Want to sponsor a post or advertise with us? Reach out to us via email.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are my personal opinions and do not represent any current or former employers. This content is for informational and educational purposes only, not financial advice. Investments carry risks—please conduct thorough research and consult financial professionals before making investment decisions. Any sponsorships or endorsements are clearly disclosed and do not influence editorial content.