👋 Hello friends,

Thank you for joining this week's edition of Brainwaves. I'm Drew Jackson, and today we're exploring:

Issues With Our Climate Mindset

Key Question: What is preventing the climate from being fixed, given how incredibly important an issue it is?

Thesis: The mindset we’ve used to approach the climate issue has only exacerbated the problem, shielding the true perpetrators from responsibility and enabling power vacuums to form wherein change—real change—will never be chosen over the desire for large profits due to the exploitation of the climate. The “we” who is responsible for climate change is a misnomer, fabricated to safeguard those who are actively preventing a just and sustainable transition.

Credit Fast Company

Before we begin: Brainwaves arrives in your inbox every other Wednesday, exploring venture capital, economics, space, energy, intellectual property, philosophy, and beyond. I write as a curious explorer rather than an expert, and I value your insights and perspectives on each subject.

Time to Read: 16 minutes.

Let’s dive in!

More often than not, it all seems like too much.

The climate issue is astronomical. The United Nations’ Security Council has labeled it as the “Biggest Threat Modern Humans Have Ever Faced.” Considering that the list includes the COVID pandemic, two world wars, and thousands of active nuclear bombs, that is a very large claim.

David Attenborough is quoted in the article as saying, “If we continue on our current path, we will face the collapse of everything that gives us security”, including food production, access to fresh water, habitable ambient temperature, and ocean food chains.

The true breadth of the crisis facing us is staggering. A recent New York Times article on the subject was aptly titled What Are You Supposed to Do With Climate Numbers Like These? Luckily, developments are happening every day around the globe.

Ever since it was identified (circa the 1800s), efforts to prevent and mitigate the effects of climate change have been ongoing throughout the globe, leading to the development of renewable energy, the establishment of yearly global climate conferences, and the expansion of public awareness efforts.

Countries, nonprofits, businesses, communities, and many more have mobilized in an effort to mount a global defense against the self-sabotaging actions of our predecessors (and ourselves).

However, there’s still a negative tone underlying the historical and future developments of the climate crisis, one that needs to be placed in the spotlight.

The story I’ll tell today is one of abuse, neglect, blame, irresponsibility, and greed. It’s not glamorous, but it’s critical to understanding and addressing our future.

All of these issues stem from our climate mindset.

Credit Outrage + Optimism

Our Climate Mindset

The climate issue is a multifaceted monster. Our mindset—the way, method, and strategy we as humans are using to address and deal with the climate—is critical to any long-term climate impacts (positive or negative).

To be clear, there isn’t just “one” climate mindset. Every person will have their own unique viewpoints on the climate and climate-related issues, collectively forming an aggregate “global climate mindset.”

Diving deeper into that global climate mindset, there is a mix of positive and negative aspects that drive policy, economies, and consumer behavior around the globe.

Climate Mindset Issue #1: The misalignment of blame, responsibility, and corrective measures within the broader global system.

A growing concern among the general population is that those who are being blamed the most for the climate disaster are not those most responsible, and as such, the “true” issues cannot be addressed.

That begs the question: Who is responsible for our current situation?

The 2017 Carbon Majors Report was an incredibly important development in the establishment of the responsibility for climate emissions. Their research found what some had started to murmur about: that just 100 companies, a small set of fossil fuel producers, have been the source of more than 70% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions since 1988.

This data, in contrast to the historical data, which primarily looked at the issue on a country-level basis, looked at the issue from a company-level to see which fossil fuel producers were the most impactful.

More than 50% of global industrial emissions since 1988 can be traced to just 25 entities, impacts large enough to significantly contribute to the effects of climate change.

Additionally, fossil fuel companies have been impacting the climate through more than CO2 emissions for decades. A 2015 report by writers at Inside Climate News dove into Exxon’s history of climate change science and news suppression, alleging that Exxon’s executives knew about climate change and the impending disaster decades before it reached the public eye.

These factors have significantly contributed to the strong public anger aimed at fossil fuel firms. According to the BBC, “many now think that such companies have said and done everything they could to be able to continue extracting and burning fossil fuels - no matter the cost.”

Focusing on the fossil fuel industry and its failure to embrace science and continue emitting far longer than it should is a meaningful start, but by no means does it capture everyone at fault, simply emphasizing where the supply chain starts.

Investigating the end consumer of the final products derived from fossil fuels, wealthier people tend to have an outsized impact on the climate through their consumption habits. A 2020 study by the University of Leeds found that the richest 10% of people around the world consume around 20 times more energy than the poorest 10%.

The study elaborates, citing that this heightened consumption is mainly due to increased transportation: flights, holidays, and big cars driven long distances.

Are rich people truly to blame for climate change? Steinberger, one of the authors of the paper, explains that this isn’t necessarily the case because these consumers live within a system that enables and rewards their consumption. Society allows them to do this; therefore, society is at the core of the issue.

Rich people often inhabit and benefit from being in rich countries, another significant source of climate change. Back in 1992, when the first international climate treaty was signed, it included an important principle: the recognition that countries had different historical responsibilities for emissions as well as varying abilities to reduce them going forward.

A 2022 CNN analysis found that the top 20 global country producers were responsible for 83% of the emissions in 2022. The following graph shows the quantity of CO2 released over time per country:

Credit CNN

Delving into the responsibility portion of this issue, given the “blame” discussed above, it’s been difficult throughout history to properly assign the responsibility of reparations to those who have caused the damage.

To start, there’s no single global authority to enforce climate action. Decisions are currently made by sovereign nations with a multitude of diverse interests and political systems, making coordinated, equitable, and effective global action incredibly difficult. Any “corrective measures” are often unilateral or weakly enforced. Some climate diplomats claim “the climate numbers are simply too large to be metabolized into policy.”

Whether or not you agree with the current system of international negotiation and the lack of true penalties, few (mainly those benefiting from their privilege in these countries) would argue against the need for richer countries, richer people, and pertinent businesses to take more responsibility for climate change.

Given the information provided above on the 100 companies responsible for ~70% of greenhouse gas emissions, you would think the responsibility would be put on these companies to change the way they operate. However, this has rarely been the case, with the majority of advertised solutions revolving around consumer choice and changes individuals can make in their everyday lives.

All of these businesses in question have been able to profit handsomely from their exploitation of the world, lacking strict penalties for any misdeeds or externalities produced by their efforts. It’s a disgusting problem, fueled by capitalist philosophies and neglected action by world leaders in favor of the benefits of fossil fuels.

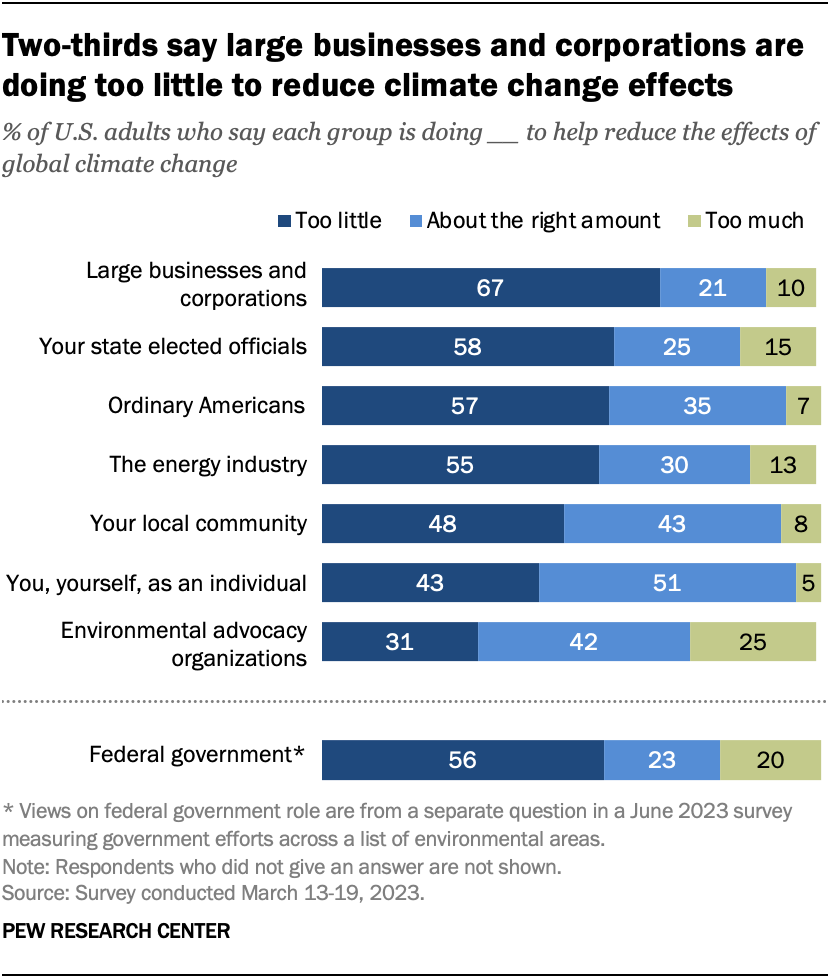

To finish, a 2023 Pew Research poll found the following information regarding consumer sentiment on businesses and their impacts on climate change:

Credit Pew Research

Climate Mindset Issue #2: Lack of true incentives and free rider problems deterring individuals and countries from addressing climate issues.

Moving on to richer people and those within richer countries, what do the statistics mean for these people? Do they need to take more responsibility for their and their countries’ emissions? Are they to blame for climate change?

These are complicated questions with even more complicated answers. Technically, these people, probably including you and me, are responsible for some portion of these issues. The products and energy we consume are linked to a significant part of these emissions.

Taking this claim as a given, each person in these countries should be doing things to minimize and eliminate their climate impact. Yet, for 99.9% of the population, their efforts on this front are minuscule in the grand scheme of things.

What’s the impact of putting solar panels on your house? Almost everyone can’t make a noticeable difference, so why should you be concerned about it? Why should you change?

For many, this is the most complicated issue with battling climate change: the incredibly complex incentive structures emphasizing free rider problems and a lack of change.

Free riders are people who benefit from something (usually a public good) without expending effort or paying for it; in other words, free riders are those who utilize goods without paying for their use.

A good example of the free rider problem would be the popular encyclopedia Wikipedia. In March 2024, 4.4 billion people visited Wikipedia, but in 2024, only 8 million people donated to support the website. The other 4.392 billion people use Wikipedia and benefit from the information therein, but do not pay to use the site.

The climate crisis poses many free-rider problems. If the air gets better for me, it also gets better for you, so spending money to clean the air creates a free-rider problem. As such, countries have an incentive not to work on the climate as they benefit from everyone else’s efforts. Clean water poses the same issues.

Countries that are making efforts to curtail climate change may become frustrated by free riders and scale back their efforts, creating a downward spiral effect wherein the final destination (the Nash Equilibrium) is that no country makes any efforts to help mitigate climate change.

Now, these factors do prove difficult to incentivize individuals to make any efforts to proactively address climate change, but there is some hope. This individualistic approach (where everyone needs to put in their own effort to mitigate their climate impact) exhibits powerful emergent properties.

Emergence is a property of complex systems, wherein the parts of the system (inputs) create a larger whole (outputs) due to their interactions. In other words, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

In this case, the efforts of individuals to improve the environment, transition to renewable energy, or switch to sustainably sourced products collectively create a greater impact on the world than the sum of the individual efforts themselves.

As such, and even without this property, every bit matters. While one household’s solar panels won’t single-handedly stop climate change, the aggregate effect of many homes adopting solar panels is substantial.

Besides lacking incentives to change, climate issues also exhibit a divergence between short-term and long-term payoffs.

The costs of climate action—investing in renewables, carbon pricing, changes in consumer behavior—are often immediate, large, and tangible, while the benefits—avoided future damages, cleaner air, cleaner water—are gentle, long-term, and harder to quantify.

This creates a strong bias towards inaction or minimal action.

Furthermore, these costs of climate action are rarely internalized into the prices of goods and services. For instance, the true environmental cost of pollution from fossil fuels is not reflected in the market prices of these fossil fuels. This means polluters don’t pay for the damage they cause, removing a key economic incentive to change.

A 2014 Brookings article discusses how the economic costs of climate change are in the hundreds of billions of dollars. A 2021 study by S&P Global found that the companies in the broad market index were responsible for ~$4T in unpriced environmental costs (around 4% of GDP for 2021).

Economists faced with this problem come to the same solution: penalize activities that cause damage to others. In this case, those responsible for polluting, heating, melting, destroying, burning, disposing, and all manner of other negative climate actions would be responsible for paying for their actions, internalizing the externalities.

However, this solution also has its issues, as discussed in Dan Ariely’s book Predictably Irrational. He talks about how if we place a price on these types of issues, a monetary value on destruction, “if a company can be charged for spewing poisons into the environment, it might well decide, after a cost-benefit analysis, that it can go ahead and pollute a lot more.” The solution he offers: make climate issues a social good rather than a monetary good.

Whether it be free rider problems, the lack of internalized externalities, or other issues, the main underlying problem with this mindset is the focus on the individual.

The University of Sydney recently found that “the energy sector is creating a myth that individual action is enough to address climate change… in shifting responsibility for net-zero emissions to consumers, we risk minimizing the accountability of larger entities that have a more substantial impact on the environment.”

Powerful entities have shifted the blame onto individuals to avoid taking the blame themselves.

Climate Mindset Issue #3: Psychological distancing to avoid addressing the true problems and the normalization of climate catastrophes.

Climate change often feels geographically, temporally, socially, and hypothetically distant.

Unless you’ve been plagued by increased droughts, flooding, tornadoes, hurricanes, glacier melt, heat patterns, wildfires, storms, or the other physical effects of climate change, you probably can’t appreciate the climate crisis for what it truly is: one of the greatest crises of our time.

The impact of climate-related events often happens and is depicted to happen in far-off places (the melting poles, remote regions, oceans, etc.). The graph below depicts an analysis by Eco Experts using data from the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index, which analyzes countries’ abilities to cope with the challenges posed by climate change:

Credit Business Insider

Some of the most populated and developed regions around the globe are those that will be least affected by climate change, so what incentive do they have to help mitigate it?

Besides purely geographical distance, climate impacts, especially the most severe impacts, are often perceived as happening far in the future, making them feel less urgent. Agreements, policies, and enactments are on the scale of years, decades, and even centuries.

For example, the Montreal Protocol, signed in 1987, was the landmark international agreement designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out ozone-depleting substances. Since its enactment, the protocol has led to a significant decline in ozone-depleting substances.

Current projections have the ozone layer returning to pre-1980 levels by around 2066 over Antarctica, 2045 over the Arctic, and 2040 globally, around a 50-70 year timetable.

Our brains are wired for immediate threats, not gradual, long-term changes. For many people, they believe that these climate effects won’t happen in their lifetime, so what is the incentive to change?

A 2018 Gallup poll found that more than 50% of Americans think that climate change won’t affect them personally, with only 45% thinking that global warming will pose a serious threat during their lifetime. Similarly, around 30% of Americans think that action on climate change is not important or should not be done.

As a result, it’s easy to become psychologically distant. The climate crisis is just one of thousands of other issues that are out there.

People often believe climate change will affect “others” more than themselves or their community. Combined with the illusion of not-in-my-backyard, these effects disincentivize climate action unless you are personally being majorly affected, which at the moment is only a small percentage of the globe.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the only bias or psychological barrier preventing us from accurately seeing, diagnosing, and addressing the climate crisis.

For instance, the constant messages of catastrophe and irreversible damage can lead to feelings of overwhelm, hopelessness, and apathy. I recently read a New York Times article titled Nobody Is Coming to Save Us, highlighting “the idea that maybe everything is pretty much our fault.”

This has led to some people shutting down, turning away, and generally losing hope in the solution, believing it’s “too late” or that individual actions don’t matter (see the discussion above).

In rapid-fire fashion, here are other factors at play:

Cognitive Dissonance: The discomfort of holding conflicting beliefs or engaging in actions that contradict one’s values. People may care about the environment but are unwilling to sacrifice conveniences or make lifestyle changes, leading to rationalizations or denial.

Confirmation Bias: Seeking out, interpreting, and remembering information in a way that confirms one’s existing beliefs or values. This reinforces pre-existing skepticism or inaction and makes it difficult to accept new, disconfirming evidence.

Sunk Cost Fallacy: Continue investing in a course of action because of past investments, even if that option isn’t optimal. Examples could be the reliance on fossil fuel infrastructure due to massive past investments.

Risk Perception Discrepancies: People often perceive risks differently based on factors like personal experience, emotions, beliefs, and cultural values, rather than purely scientific data.

Bystander Effect: The assumption that someone else will deal with the crisis: governments, scientists, other countries, etc.

However biased our perceptions of the climate may be, there are still some positive aspects. For instance, 56% of people globally say they are thinking about the climate and its issues daily or weekly. 63% are beginning to take climate change impacts into consideration when making decisions like where to live or work and what to buy.

These deeply ingrained psychological barriers, from the disarming effects of distance to messages of doom and gloom, combine to prevent a global sense of urgency.

While polls suggest a growing awareness and even some behavioral shifts, the data also reveals a persistent disconnect between recognizing the problem and feeling personally compelled to act decisively.

Until the impacts become undeniably immediate and personal for a critical mass, or until more effective strategies emerge to bridge this psychological gap, the global mindset will remain a formidable challenge to effective climate action.

Credit New Scientist

The Core Climate Issue

Climate scholar and author Genevieve Guenther writes,

The “we” responsible for climate change is a fictional construct, one that’s distorting and dangerous. By hiding who’s really responsible for our current, terrifying predicament, [the pronoun] “we” provides political cover for the people who are happy to let hundreds of millions of other people die for their own profit and pleasure.

Who is this “we”? Does it include the 735 million who, according to the World Bank, live on less than $2 a day? Does it include the approximately 5.5 billion people who, according to Oxfam, live on between $2 and $10 a day? Does it include the millions of people, all over the world (400,000 alone in the 2014 People’s Climate March in New York City) doing whatever they can to lower their own emissions and counter the fossil-fuel industry?

Shifting our mindset, instead of thinking of climate change as something “we” are doing, think about the billions of people on this planet who would rather preserve civilization than destroy it with climate change, who would be willing to forego many of their privileges to enact change, who would rather have the fossil-fuel economy end than continue polluting to the ends of the earth.

The New York Times article discussed above, Nobody Is Coming To Save Us, is very clear on this point: “One of the biggest issues, I believe, with the current global narrative on climate change is that it's (deliberately) abstractly big. It is, therefore, no fault of anyone in particular. By speaking of climate change in the way that we do, we give ourselves permission to ignore it, convincing ourselves it is someone else's problem. And, if climate change is someone else's problem, it is definitely up to someone else to fix it. But the brutal truth is that we are the only ones here."

Conversely, there are others, a smaller group, many of them at the echelons of businesses, governments, and other prominent organizations throughout the world. These people seem to be willing to destroy civilization and let millions of people die in the pursuit of profits and power. As Guenther puts it, “We know who those people are. We are not those people.” She elaborates:

Complicit people and institutions must be called out and encouraged to change. And the fossil-fuel industry must be fought, and the governments that support the fossil-fuel economy must be replaced. But none of us will be effective in this if we think of climate change as something we are doing. To think of climate change as something that we are doing, instead of something we are being prevented from undoing, perpetuates the very ideology of the fossil-fuel economy we’re trying to transform.

If you boil it down, this is the core issue with our climate mindset.

If you can only afford a home on the outskirts of town where there isn’t access to public transportation, is it really your fault for becoming dependent on a car? In the University of Leeds study, the author, Julia Steinberger, writes, “Just because you can allocate [emissions] to an entity or to a location in a supply chain, does not mean that the power of agency lies with that entity or that location in the supply chain. If you’re thinking about these supply chains, are you going to say that final consumers actually have the final decision-making over everything that happens upstream? Who is actually taking the damaging decision?”

Succinctly, the problem is this: the countries, businesses, people, entities, and other organizations that have the greatest historical responsibility for climate change continue to have the greatest influence on the climate response, enabling them to easily abuse their power.

Ultimately, these insights dismantle the comfortable fiction of a collective “we” as solely responsible for the climate crisis. The true power dynamic lies with a distinct minority: those at the highest echelons of the fossil-fuel industry, those profiting from the exploitation of the climate, those who directly benefit from these goods and services, and the complicit governments that actively enable their continued, profitable destruction of the climate.

By attributing blame broadly, we inadvertently grant political cover to the very entities who stand to lose most from meaningful change, and who wield disproportionate influence over the global systems.

Effective climate action is not just about individuals making marginal sacrifices, it’s mainly about confronting and transforming the concentrated power that actively prevents a just and sustainable transition, forcing a true reckoning with who holds the keys to our collective future.

That’s all for today. I’ll be back in your inbox on Saturday with The Saturday Morning Newsletter.

Thanks for reading,

Drew Jackson

Stay Connected

Website: brainwaves.me

Twitter: @brainwavesdotme

Email: brainwaves.me@gmail.com

Thank you for reading the Brainwaves newsletter. Please ask your friends, colleagues, and family members to sign up.

Brainwaves is a passion project educating everyone on critical topics that influence our future, key insights into the world today, and a glimpse into the past from a forward-looking lens.

To view previous editions of Brainwaves, go here.

Want to sponsor a post or advertise with us? Reach out to us via email.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are my personal opinions and do not represent any current or former employers. This content is for informational and educational purposes only, not financial advice. Investments carry risks—please conduct thorough research and consult financial professionals before making investment decisions. Any sponsorships or endorsements are clearly disclosed and do not influence editorial content.